|

| Anglo Saxon History |  | |

| | Old Winchelsea an elegant explanation |

|---|

| | |

|---|

| Winchelsea - what does the name mean ▲ |

|---|

Having researched Saxon place names for a long time my belief is that Saxon place names either describe the place's location or what it was known for making.

In the case of Winchelsea the name would appear to be made up of three snippets.

the first snippet now pronounced 'Win' probably originated from the Saxon 'þwang' pronounced thwang which means a thong.

the second snippet pronounced 'chel' probably originates from the Saxon 'cisil' usually pronounced chesil which means shingle or gravel.

the final snippet pronounced 'sea' probably originates from the Saxon 'æg' pronounced 'ey'

So the final translation becomes thwang chesil ey the th would be dropped then becomes Wangchesiley which over time can render into Winchelsea.

Therefore the meaning of the name becomes the thong(long thin) chesil(shingle) ey(island)

Therefore the name Winchelsea translates to The long thin shingle bank island - interesting

| | Documentary evidence ▲ |

|---|

John Leland – Itinerary (c. 1540s)

“The olde towne of Winchelsey is clene destroyed by the se.”

"Then in the tyme of the yere aforesayde the king set to his help in beginning and waulling New Winchelesey: and the inhabitantes of Olde Winchelesey tooke by a litle and a litle and buildid at the new towne. So that withyn the vi. or vii. yere afore expressid the new towne was metely welle furnishid, and dayly after for a few yeres encreasid."

Edward Hasted – History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent (1799)

“In the year 1287, on the eve of St. Agatha the Virgin, the town of Winchelsea was drowned, and all the lands between Cleimden and Hythe.”

Holinshed’s Chronicles (1577)

“In the year of our Lord 1250, on the first day of October, when the moon was upon her change, it appeared of a fiery red color and was greatly swollen, presaging a fearful tempest that was to come.

Soon after, there arose a mighty and violent storm with such fury and strength that the sea was driven against the coast with great force. At Winchelsey, a town famed for its port and trade, the waves broke over the shore and overwhelmed the land. Bridges and mills were shattered, sea banks and dikes gave way, and many buildings were utterly destroyed.

Not fewer than three hundred houses, along with several churches, were drowned beneath the rising waters. The devastation was so complete that the town was rendered uninhabitable, forcing the survivors to abandon it.

This calamity was not isolated; many other coastal towns along the southern shores suffered grievously by the sea’s assault, losing both goods and lives. The destruction of Winchelsey was of such consequence that it was deemed necessary by the crown to found a new town upon higher ground, thus giving rise to New Winchelsea.”

William Camden, Britannia (1610 English Translation by Philemon Holland)

"Thence the shore retires backwards, and is hollow'd inwards, being full of many windings and creeks, within which stands Winchelsea, built in the time of King Edward I, when a more ancient town of the same name, in Saxon Wincelsea, was quite swallow'd up by the raging and tempestuous Ocean, in the year 1250. (At which time the face of the earth both here, and in the adjoining coast of Kent, was much altered.)"

"Situate it is upon a very high hill, very steep on that side, which looks towards the sea, or overlooks the Road where the Ships lie at Anchor. Whence it is that the way leading from that port to the haven, goes not straight forward, lest it should by a down-right descent force those that go down to fall headlong, or them that go up to creep rather on their hands, than walk: but lying sideways, it winds with crooked turns in and out, to one side and the other."

| | Most likely location of Old Winchelsea ▲ |

|---|

There are a few pointers to this, the 2018 Wessex Archaeology Dive:

Confirmed ship timbers and harbor debris at 50°55'N, 0°43'E. This equates to a latitude /longitude of 50.92136, 0.76908 which places it about 0.7km off the current shore line.

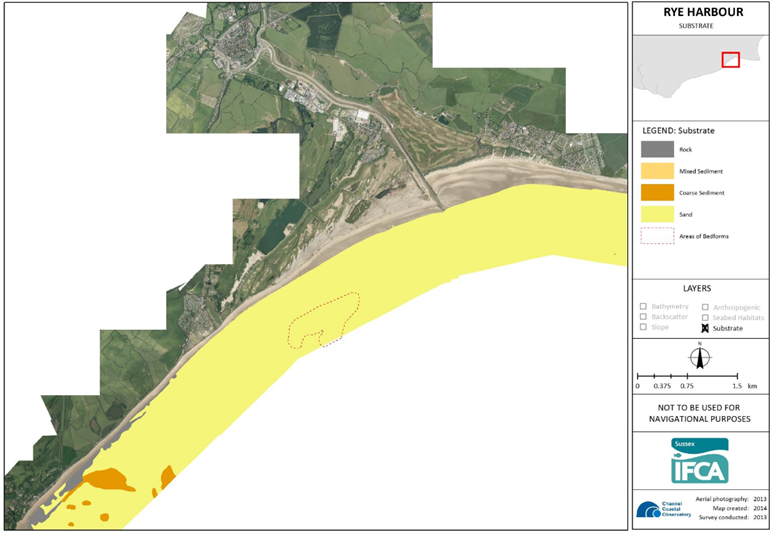

The Sussex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority have carried out seabed mapping for the area from Dungeness to Selsey, the following map shows the Rye Bay area.

|

Please click on the image to see the original document

There is an interesting area shown called 'Areas of Bedforms' shown as an outline on the map, this implies that there is a harder land formation under the bedform, as bedforms are in effect ripples in the seabed.

If this is the case then that area of harder ground could provide a reason for a high shingle bank being created to the north east of this as the prevailing wind is from the south west, and this harder ground would provide a good defence against the sea and the weather and protect the shingle bank where Old Winchelsea was located.

The next map shows my interpretation of the landscape in Saxon/Norman times.

| | What is a bedform ? ▲ |

|---|

An area of bedform refers to a region or surface covered by bedforms, which are sedimentary structures shaped by the movement of fluids (such as water or wind) over loose sediment (like sand or gravel). Bedforms are common in rivers, oceans, deserts, and other environments where sediment transport occurs.

Examples of Bedform Areas:

- Ripples – Small, wave-like patterns in sand (common in streams, beaches, and deserts).

- Dunes – Larger, elongated ridges found in deserts (aeolian dunes) or underwater (subaqueous dunes).

- Megaripples – Intermediate in size between ripples and dunes.

- Antidunes – Bedforms that move upstream in high-energy flows (e.g., fast rivers or tidal channels).

- Cross-bedding – Layered sedimentary structures formed by migrating dunes or ripples.

Where Bedform Areas Occur:

- Fluvial (Rivers & Streams): Ripples and dunes on riverbeds.

- Marine/Coastal: Sand waves and dunes on the seafloor.

- Aeolian (Deserts): Sand dunes formed by wind.

- Glacial Environments: Subglacial bedforms like drumlins.

The size and shape of bedforms depend on factors like flow velocity, sediment grain size, and water depth. Studying bedform areas helps geologists and engineers understand sediment transport, erosion, and deposition processes.

| | Bedform development on the sea floor ▲ |

|---|

Subaqueous Dunes Overlying a Mud-Dominated Stratum

Other Locations:

- Tidal channels (e.g., North Sea, Bay of Fundy)

- Continental shelves with strong currents (e.g., South China Sea)

Process:

- Lower Layer (Harder/Cohesive Substrate):

- A muddy or clay-rich layer (formed during low-energy conditions) becomes compacted and slightly cohesive, acting as a firmer base.

- Over time, this layer may even develop into siltstone or shale if buried and lithified.

- Upper Layer (Sand Transport & Bedform Development):

- When currents strengthen (e.g., from tides or storms), sand is transported over the muddy layer.

- Large subaqueous dunes (wavelengths of meters to tens of meters) form due to the interaction between the mobile sand and the cohesive mud below.

Preservation Potential:

If buried, these dunes can create cross-bedded sandstone overlying finer shale/mudstone—a classic example of stratified sedimentary beds in the rock record.

Effect:

- The mud layer resists erosion, forcing dunes to migrate primarily by sand avalanching (slip faces).

- The contrast in erodibility between sand and mud can lead to sharp basal contacts in geological outcrops.

Other Examples of this mechanism:

- The Taiwan Strait

- Mobile Sand Dunes (Upper Layer):

Composed of medium to coarse sand transported by tides.

- Firm Mud Layer (Lower Layer):

A compacted, cohesive mud deposit (silt/clay) formed during quieter hydrodynamic conditions. Acts as a semi-resistant base, preventing full erosion and influencing dune morphology.

- North Sea

- Amazon Basin

These Examples:

- Show how stratification controls bedform dynamics—the sand dunes migrate over the mud, but the underlying layer remains intact.

- And also mimics ancient sedimentary records where cross-bedded sandstone overlies shale.

|

This map shows my explanation for Old Winchelsea as a long lasting feature in the Rye Harbour area, it shows the area in Saxon/Norman times between the 566AD Storm and the 1287AD Storm which destroyed the island.

The Cliffs at Fairlight were about 1 km further south towards France(see our Landscape - The Cliffs of East Sussex and Erosion 450-2024AD) and further east towards Dover by about 1.5 Km. This meant that the shingle and gravel banks now found near Winchelsea Beach were about 1 Km further out into Rye Bay.

The small house icon shows the position of the wharf timbers, the dark orange the island, the lighter orange area, gravel and sand. The green areas show harder land and cliff areas, with the dark blue areas salt water, and the pale blue salt marshes.

The small area on the previous map showing 'Areas of Bedform' implies an area of harder material under the sand, this is shown as a small green area in the larger pale orange area. If this were the case and this were above high tide level until the 1287 storm then a shingle bank would build up behind this harder material away from the prevailing wind, which in this area is South West, hence the shingle bank builds up to the North East.

To make this shingle bank an island as per the Winchelsea name, then the orange area around the shingle must have been washed over by the sea at high tides.

|

Rye harbour area bathymetry ▲

|

|---|

This is a map of the current seabed from the European EMODnet viewer - pleas click on the image to visit their website.

Another site with some interesting geological explanations of spit's, bars and tombolos is SaveMy Exams

| | |

|---|

| Theoretical Conclusion ▲ |

|---|

The current Winchelsea Beach area is a spit of gravel produced from the cliffs at Fairlight, that goes to Rye harbour, behind the spit is an area that used to be salt marsh.

As erosion takes place at Fairlight, so the spit moves backwards towards modern Winchelsea. This is currently prevented by the sea defenses all along this coastline.

If we interpret the 'Areas of Bedform' as an area of harder material under the sand, hard clay or sandstone, then a more permanent gravel area would form on the leeward edge of this material.

This harder area would have been protected from the main force of the sea and the weather coming in from the South West by the cliffs at Fairlight/Pett.

If this harder area was exposed by the storm of 566AD then it would slowly be eroded away on its seaward edge by storms, but not by the normal tides due to the protection provided by the cliffs. The sea would continually wash the island away, but the long shore drift which in this area sweeps the shingle on the coast to the East would continually be building up the island.

Hence this would be a thong of shingle hidden behind a harder island of clay, which in turn was hidden by the cliffs, with longshore drift continually building the island.

The storm of 1250AD would have collapsed some of the cliff at fairlight hence moving the protective shingle bank further back exposing the harder area to quick erosion by the sea. the 1287AD storm would have then washed away the protective harder area and hence Old Winchelsea.

To make Old Winchelsea into an island, then the tides would need to pass over this spit at high tides.

| | Other Documents ▲ |

|---|

The main reference to the history of the manor of Rameslie was written by Keith Foord and available from the Battle and District Historical Society(BDHS) website.

It is worth reading Jeremy Haslam's 'The site and early development of Old Winchelsea, East Sussex'

Also an old book by William Durrant Cooper has some old references

The History of Winchelsea(pre 1895)

Why Winchelsea is not refered to in Roman times as OLD WINCHELSEA (Sussex) and DUNWICH (Suffolk) – 1287 - by E.P.Dennis

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Local Interest

Just click an image |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|